Not having his dad here colours Hugh’s life: “it’s a little bit of everything”

There are times when Hugh McClure feels like screaming from the rooftop, so that everyone can know about the wonderful person that his dad was, and how much he misses him.

“Dad just had the X-Factor,” says Hugh, a 24-year-old researcher at the Australia Pacific Security College in Canberra.

“He could make anyone laugh and everyone felt at home around him. I don’t think there was anyone that he couldn’t strike up a conversation with. He had a nickname for everyone and always had a funny story up his sleeve to tell them.

“But more than just a fun person to be around, my dad loved like a rock. A devoted husband, a loving son, a generous friend, a great brother, and, to my sister and I, an incredibly proud father who never let us doubt that he loved us beyond measure,” said Hugh.

“Dad shared this love with all he met. He was a police officer who had the community at heart. He was a musician who loved nothing more than seeing his friends and bandmates succeed.

“And if he ever heard about someone who fell on hard times, he would organise a charity bike ride, a multi-day walk, or a music tribute concert to raise money and lift spirits. Nothing was ever trouble for Dad and he was the first person to help out.

“I feel like shouting from the rooftops that our world has lost a true hero.”

But despite the many achievements of his dad’s life, Hugh says it was “the little things in life”, such as music, kayaking and being in nature, that mattered most to his dad, “the things that bring joy to every day”.

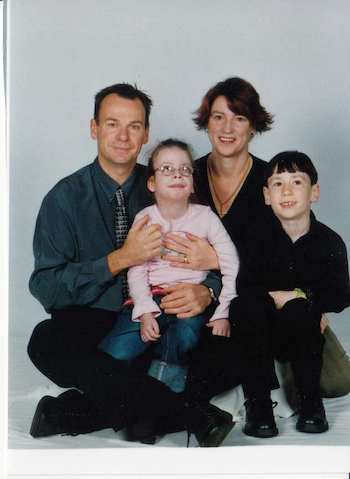

“When I’ve dreamt about Dad, we’ve always been at home, sharing the little moments as a family. My family will always be the four of us: my dad, Stephen, my mum, Tricia, my sister, Jordan, and me.

“Cause it’s the little things in life, that make you feel just right,

they make you feel right”

Chorus from the song ‘Little Things in Life’ by Stephen McClure

“My sister passed away in 2009, when she was 15, and my dad 10 years later in 2019, after having non-Hodgkin lymphoma. My mum and I are a team.”

The importance of others sharing memories of his dad

“I like hearing about how my Dad’s memory lives on in others,” said Hugh. “It’s nice when a friend comes over for a dinner party and shares a story that they remember about him or puts one of his songs on.

“For me it’s that feeling that he’s not forgotten and that he endures, and that there are other custodians of his memories,” Hugh explained.

“When you’ve lost someone, you feel like you are the keeper of their spirit. I’m worried that there are things I will forget.

“But despite these gestures and memories told, the reality is that I am more aware, and Mum is more aware of Dad’s lack of presence than anyone else,” he said.

“While people care, I think it’s hard for others to know the extent to which the world has stopped turning. That every day I wish he was here – just to tell him about my day, and to hear a new story.”

Hugh said he misses his dad’s constant influence and leadership in his life; how he made him break rules, loosen up, but also feel more secure.

“So, while people can bring him up once in a while, the reality is that two years on, folks assume everything is back to normal and on its even keel. And looking from the outside, potentially it is.”

Regular conversations with a counsellor helped

“Life can be really busy, and we can push our emotions down in order to just get through the day.

“It’s really nice knowing that once every three weeks, I have an hour where I can talk about Dad – I am often itching to just tell someone about him. I think without counselling I would feel building unease,” said Hugh about his regular conversations with Leukaemia Foundation grief and bereavement support coordinator, Donita Menon since his Dad’s passing in March 2019.

“Our friends and family aren’t impartial spectators. When they ask how we are, they want us to say that we are going well – because they want us to be happy. That’s why it’s good to talk to someone neutral, with whom you can be really honest.

“And I think it’s really nice knowing that there’s that set time when that conversation happens.

“The conversations vary widely, they vary with what is needed, but that’s really good.

“It’s good to talk about the broader implications. Every other relationship of mine is changed by losing Dad as well.

“My relationship with Mum is different because there’s two of us now. I also have a different relationship with my grandparents, and my interactions with my friends have changed, because I have gone through something which they haven’t, so being able to talk through that and know how I can approach other people, is really useful.”

It was Hugh’s mum who put him in touch with Donita after the Leukaemia Foundation reached out to her.

“Mum had an initial call with Donita. She told me it was really useful, and she thought it might be something worthwhile for me,” said Hugh.

That was in mid-2019, three months after Hugh’s dad’s death on March 9. Since his diagnosis four years earlier, Stephen had had treatment after treatment – radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and a stem cell transplant.

Hugh was optimistic about his dad’s health until the end

“Throughout my dad’s illness I saw a man who was determined, a man who was healthy. He’d ridden his pushbike from Darwin to Adelaide, and from Perth to Adelaide.

“More than that, he was just a good man; he didn’t deserve not to have a retirement. I thought if anyone could defeat his illness, it was him. I couldn’t picture a world without him in it,” Hugh explained.

Reflecting on how Hugh saw his father throughout his battle with cancer, he said, “even though he was constantly fatigued from treatment, he did not let the disease stop him from living life”.

“He played concerts at folk festivals to hundreds of people, he continued to go kayaking, and he volunteered assisting adults with a disability.

“He wasn’t going to be defined by his illness and he made the most of every day.

“My sister, Jordan, passed away when she was 15. She was the most tenacious person I have ever met; she was strong and beautiful. I have always been in awe at her, and I see that Dad had her same strength.

“But I’ll always remember the moment when that changed. It was February 25th, the day after Dad’s 59th birthday when we learnt that the lymphoma had entered his brain, and CAR T-cell treatment was no longer an option.

“The medical team told us there was nothing to be done. Nothing can ever prepare you for that conversation,” Hugh said.

Hugh’s journey with grief begins

“You vanished, like footprints in the sand, the waves attacked

And memories are all I have, at night to keep me warm

And I live in hope, that one day you will return

Ooh you don’t come here anymore”

Verse 1 of You Don’t Come Here Anymore by Stephen McClure

Hugh described the early months as feeling “like when you have been away on holiday for a bit too long, and you’re ready to go home and have everything feel normal again”.

“I did all those things that people say happens after someone has died… I went to call him on the tram after work, and I kept on thinking of things to tell him. But even now, two years later, it often feels like he’s still just about to walk up the front steps at home in Wollongong, like he’ll come home from the shops any minute.

“And you realise that you actually can’t ever just feel normal.

“I remember seeing cards from friends that said, ‘Trish and Hugh’, and I thought to myself, there are names missing off that envelope, that’s not our family.

“You’re just waiting for it to feel like you’re back at home again, and you can’t get that.”

Since then, there have been waves of grief, and Hugh reflects on a song played at his father’s funeral – a song called A Little Bit of Everything.

“It’s the mountains, it’s the fog; it’s the news at six o’clock, it’s the death of my first dog”.

And there’s a song by the Australian singer, Fanny Lumsden, which resonates with him too.

“It’s all pretty simple, some things don’t change with time: I’ll always be wishing you were here, and that’s a wish that will always be mine”.

“In grief, my relationship with my Dad’s parents, my paternal grandparents, has been so important,” said Hugh.

“For them, losing their devoted and loving son has been so difficult, and sharing memories of his childhood and his life has been absolutely key. I love them very much and am thankful for the way that they love my mum.

“I see so much of Dad in his parents, Nan and Pop, and his siblings, David and Melissa, and I also see Dad in his wonderful friends.”

Decisions around stopping and restarting counselling

Six months after Hugh lost his dad, he thought he should stop his appointments with Donita.

“I thought, ‘okay, well, maybe that acute moment’s gone. There’s a lot of people out there in need. I’ll finish that’,” Hugh explained.

“But then I went through a period where I did really struggle quite a lot. Mum encouraged me to recommence [counselling] after a six-month break.

“Grief has a very long tail and it affects every part of your life every day, in one way or another.”

“Keeping the relationship going with Donita has been essential to staying afloat. I am very thankful to her and the Leukaemia Foundation for the support she has given our family,” said Hugh.

“Beyond the acute moment, there are a thousand moments which ache because he is not here for them.

“Since he’s been gone, I have bought my first house, graduated from university, and changed jobs.

“Something Donita and I talk about is that when you lose someone, you don’t just lose them once. Their death isn’t a single event, but rather you lose them again, and again, in each of those moments that they are not there for.

“I would say to anyone considering counselling, that it is particularly useful because even though you may have loved ones who share your loss, your grief journey is not the same as theirs. There are different things that cut more deeply for Mum and I, and we are at different points in our grief. It’s not a linear thing.

“I remember last year; I was just about to sit the final microeconomics exams of my degree. It was during travel restrictions and I hadn’t been able to go home to Wollongong and see Mum in six weeks. At that point she was really struggling, and I was distracted.

“And at another time, this year, I was just in a really, really, down space; a period of time where I’d go for a walk and cry every day. Everything felt lonely. I was struggling, and I felt like I’d lost my closest supporter and the person who could make me feel safe. But this time, Mum was in a different space.

“These things aren’t linear, so speaking to Donita is really helpful for us both,” Hugh said.

“Not everyone is going to be mentally well all the time. This is a really big thing. Grief is exhausting, it colours everything, and it’s not a set, linear thing. It evolves, it moves, and it continues to come up and down.

“But I’ve never hung up the phone to Donita and thought, ‘well, I feel worse for doing that’.

“Sometimes I’ve felt absolutely bereft, and I’ve felt exhausted, and I’ve thought, ‘I cannot go into the office this afternoon, I’m going to have to work from home’, or, ‘I need to take an hour or two, to go for a walk, I can’t go back and study’.

“But I’ve never gone, ‘gee, that was a waste of time’. Looking after your mental health is never a waste of time.

“I think identifying and thinking about your feelings, and reflecting on them, can be really useful.

“And there are things that I wouldn’t have thought about doing that Donita has encouraged,” said Hugh.

“In hospital, medical teams will ask people those standard questions to assess their memory. It was the same for Dad. ‘Who is the Premier?’, they might ask, and sometimes they’d ask, ‘what does Tricia do for a job?’, or ‘how old is Hugh?’ and his answer was ‘21’.

“But when I wasn’t 21 anymore, all I could hear was Dad answering those doctors, saying ‘Hugh is 21’.

“I realised that this was the last stage that he knew me at. I really struggled with turning 22 and I struggled with changing my job for the first time, because as the world turned, I was moving further away from Dad.

“In my head, as I approached 22, my life with Dad felt like it was drifting further and further away, and I couldn’t reach back to him, and the person he made me.

“It’s really hard to comprehend that our new stories end there. There aren’t new photos to share, new songs to listen to, new holidays to make memories on. That’s it. The finality has never felt real,” said Hugh.

Donita suggested Hugh keep a journal.

“And every day I was 22, I would write something to him, and it would just be about Dad and me, and our relationship. One day I might put some song lyrics in or another day it might just be a picture,” he said.

“There have been other things Donita has suggested I do that would be cathartic, including writing different letters at different points in time, that I wouldn’t have otherwise considered and that have been helpful.”

Marking key dates since his dad’s passing

Both Hugh’s sister and his dad had died at the family home, which he said, “was a decision that we made as a family”.

When Hugh shared his story with Living Well With Grief, his dad would have had two birthdays, two anniversaries, and two Christmas’s since his death in March 2019.

“As far as his birthdays have gone, Mum and I have taken the day off on both of them and tried to do something, and on both times the universe had other plans – reminders that everything just feels a little bit wrong without him and the role he played in looking after us.”

In concluding, Hugh said grief was “such an enormous, heavy thing. It’s a wound you carry”.

“My dad was 59. I was 21. My mum was 57. I felt enormously robbed for us. For my parents’ retirement, and for all the moments that Dad will never be here for; I still feel enormously robbed. This is not how life was supposed to look. There are a lot of things to unpack and to process, and grief can make you so tired. So having someone to acknowledge that, and to talk to you about that, can be really helpful.

“To people reading this who might be in touch with the Leukaemia Foundation, it can be really helpful to have conversations. That would be my only advice – these conversations are useful.”

Share your own blood cancer story

Every person touched by blood cancer has a unique and important story to tell. Stories are our most powerful tool to spread awareness of blood cancer, to inspire others going through a diagnosis and to encourage support from the wider community.