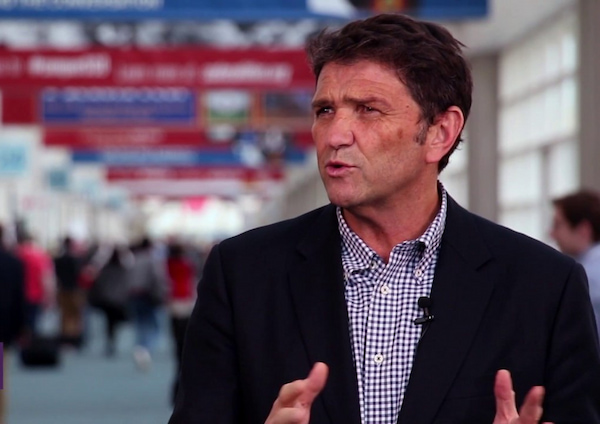

Expert Series: Professor Miles Prince – the challenges, the treatments, the future of myeloma

Professor Miles Prince specialised in haematology because he wanted “a long-term relationship with his patients, to have a positive impact on their lives, and a chance of curing some patients”, as well as research opportunities. It was the 1980s and there was a lot of research involving leukaemia, lymphoma and myeloma. “It seemed a very exciting field” said the professor at Melbourne and Monash universities, who also is Professor/ Director of Molecular Oncology and Cancer Immunology at Epworth Healthcare. He has a special interest in myeloma and is a member of the Blood Cancer Taskforce.

Not only is Professor Miles Prince “a true believer in CAR T-cells”, he believes they may even have the potential to cure myeloma one day.

“Quite frankly, if we’re going to cure myeloma, it’s approaches like CAR T-cell therapy that are going to find us there. It’s incredibly exciting,” said Prof. Prince.

“I think CAR T-cells definitely have the potential to cure patients.”

“My holy grail would be to use it very early in the disease, when the patient’s own immune system is at the optimum.

“CAR T-cells are going to find a place in myeloma, for sure, a big place, but we’ve got some challenges because of the toxicity and the cost, which would need to be viable.

“Right now, it’s being used right at the end of treatment, as end stage, so we’re not curing people. But it will be used earlier and earlier, and that’s hopefully where CAR T-cell therapy will have its biggest impact.”

New drugs in the pipeline for myeloma

Another new group of drugs Prof. Prince describes as “really exciting and finding its way forward” are directed against the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) on the surface of plasma cells, and uses a way of binding on to BCMA.

“Just like daratumumab (Darzalex®) is a monoclonal antibody against CD38, there are a number of potential targets against BCMA,” he explained.

The first of these are the antibody-drug conjugates and the first one, belantamab mafadotin (Blenrep®), combines the antibody against BCMA to an immune toxin to access the myeloma cell.

“It’s TGA-approved and is already going through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) and hopefully will get reimbursed,” said Prof. Prince.

Belantamab mafadotin is available through a compassionate scheme in Australia.

“The second are what we call BiTE antibodies and there are a number of them. They’re BCMA-linked to T-cells via a dual antibody; one binds to BCMA and the other binds to the T-cells. It drags the patient’s own T-cells to the myeloma, and can be very effective.

“There will be a lot of studies around BiTE therapies, which work in a similar way to CAR T-cell therapy, and are a good competitor to CAR T-cells.

“The big question in the next few years will be, ‘what is superior, BiTE therapies or CAR T?’,” said Prof. Prince, who emphasised the importance of this question, because BiTE therapies are a more ‘off-the-shelf’ treatment and potentially cheaper in the short-term.

“The sooner we get more of these immunotherapies–the CAR Ts, the BiTE antibodies, the antibody drug conjugate balantamab mafadotin–into trials and patients, that will be very exciting.”

“The most effective drug, not necessarily the cheapest, is ultimately the one that will win out.”

“CAR T-cells have shown very high effectiveness and response rates in patients, so it’s probably the frontrunner between the two, but the proof will be in the trials.

“CAR T-cell therapies have already found a place in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, large cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma, and have just been approved in the United States for myeloma,” said Prof. Prince.

There are different CAR T-cell products and the trials have been slightly different.

“Some of them have had dramatically high response rates,” he said.

“It’s going to be a matter of which is the best one and when to use it, based on the toxicities and the cost.”

However, although they’re immune-based therapies, they’re not without their risks.

“CAR T-cells can cause neural toxicity, they can suppress the immune system, they can cause what is called CRS or cytokine release syndrome, so we have to be very careful about how we use them,” said Prof. Prince.

“Just because they’re effective and they’re immune therapies and they’re not ‘chemo’ doesn’t mean they’re not without side effects.”

Monoclonal antibodies – the most recent gamechanger in myeloma

Prof. Prince said the “biggest gamechanger in myeloma” in recent years were monoclonal antibodies, namely daratumumab, which, when used at first relapse is seeing patients “go into their first and deepest remission–a scenario which turns the tables”.

“The first remission is the best remission.”

“There’s also rapidly accumulating data that daratumumab, when used as a frontline treatment, will give deeper remissions, and it’s definitely improved the outcome for the elderly.

“Eventually, I think daratumumab will be used frontline for a lot of people and they might get really deep and long first remissions – five to seven years, instead of three to five years [for just chemotherapy as first-line treatment].

“I think that is going to be the next big PBAC approval with daratumumab, as frontline for the non-transplant eligible,” said Prof. Prince.

Daratumumab was listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), on 1 January 2021, in combination with bortezomib (Velcade®, a proteasome inhibitor) and dexamethasone as a second-line treatment for myeloma patients, which Prof. Prince found “disappointing”.

“We would have loved to have seen ‘a world’ where people could partner daratumumab with both a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent (IMiD) [e.g. thalidomide, lenalidomide, pomalidomide].

“There’s good data from the Pollux study, so we know daratumumab works really well with lenalidomide (Revlimid®), but unfortunately it’s not approved.

“Unfortunately, the PBAC has only allowed a partnership with a proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib.

“It means, as physicians, our hand is forced with that combination,” said Prof. Prince.

“We’d also love to see daratumumab combined with carfilzomib (Kyprolis®) [a second-generation proteasome inhibitor], but of course we await the data [from clinical trials].

“This means it’s a bit like the tail wagging the dog on how we treat people upfront, knowing what’s available at first line and the only time we can use daratumumab must be when it’s with bortezomib.

“On a positive note though, the PBAC has approved daratumumab where it is most effective; first relapse. Where we know that the median progression free survival is beyond two years at that first relapse and people can get a deep response.”

About myeloma

After non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma is the second most common blood cancer and makes up 1.6% of all cancers. There are around 20,000 Australians living with myeloma, with 2330 new cases diagnosed and 1000 deaths each year.

“We’ve got a lot to learn about the causes of myeloma,” said Prof. Prince.

This disease, which has taken off since the Industrial Revolution, is probably strongly influenced by environmental factors, a mixture of geographic and some genetic influences which we don’t as yet understand.

Prof. Prince gave the example of myeloma being the most common blood disorder affecting black Africans, both in Africa and in the U.S. and he said myeloma is also “extremely common around the Mediterranean”.

In terms of increasing incidence, Australia is “very close to leading the world”, Prof. Prince said.

“That’s probably due to the combination of having a good health system, in terms of screening for patients, and our mixed cultural background.”

Everybody with myeloma goes through the monoclonal gammopathy and smouldering myeloma stages prior to, ultimately, end organ damage with a formal diagnosis of myeloma, but timeframes differ. Development of the monoclonal protein through to myeloma that requires treatment, “can take anything from a few years to a few decades”, he said.

Risk stratification, defining myeloma subgroups and monitoring myeloma

The “most difficult thing”, Prof. Prince said, is giving a patient “some idea of what our expectations are” for them.

“There’s a subgroup of patients that we know are going to do really badly, that will probably not survive more than a couple of years, but that’s a relatively small proportion, less than 10%,” Prof. Prince explained. These include those with poor chromosomal genetic categories, those with renal failure, and those who are very old where treatment choices become limited.

“The remaining 90% we try to risk-stratify, regarding how well they will do given the median survival of myeloma is seven years.

“All of us have some patients living well to 10 years and beyond, and some who don’t get beyond four years.

“I’ve got patients who’ve had their original treatment, a transplant, and remained in remission post-transplant for a good seven to 10 years.”

Prof. Prince said one of the biggest challenges in myeloma was defining those patients who fall into these two groups; those who survive for up to around four years, or those who may well live beyond seven years.

“The advances we have made in myeloma are not just because of the new drugs, but the way we can monitor the disease,” he said.

“We need to define the patients with smouldering myeloma who don’t require treatment.”

“You can buy some time early on in the disease by monitoring patients closely.

“With new scanning techniques, the use of MRIs, PET scans, better assays, and more accurate paraprotein estimation, we’re able to work out when patients require anti-myeloma treatment. That sometimes can put that treatment off for three to five years, and that has an impact on survival,” he said.

“Then we treat the patients, and with careful monitoring we might be able to see their disease returning and work out when those patients require their next treatment.

“Meeting progression criteria doesn’t always equal immediate therapy, so you can buy quite a few years by monitoring myeloma in a cleverer way,” explained Prof. Prince.

He said the first and second remissions were important, and once a patient is on to their third line of treatment, “things are harder for the patient”.

“We’ve had a good improvement in their second remission with some of the new drugs.

“That’s a little truer for the older patients, where it is always harder in someone who’s elderly with their second line therapy, simply because of their tolerance.

“There’s a philosophy in myeloma… to move all your best drugs up early.”

“So, some of the treatments we’re now using in second line, like the monoclonal anti-CD38 antibodies [daratumumab], we’ll be using at the frontline in a few years.”

The myeloma treatment paradigm and side effects

“Upfront therapy is all about a balance between efficacy and tolerability,” said Prof. Prince about the possible choices, combinations, and sequence of drugs with up to 15 options.

He considers the treatment core to be the proteasome inhibitors, the IMiDs, and daratumumab.

“For young patients, it’s become a no-brainer,” he said.

“Those who are transplant-eligible should be getting triplet therapy, namely a proteasome inhibitor, and in Australia it’s bortezomib, plus lenalidomide with dexamethasone as pre-transplant treatment, and then lenalidomide maintenance.

Those who are non-transplant eligible require the treating doctor to decide what treatment combinations the patient will tolerate – a triplet, a doublet or a single agent.

“The treatment paradigm in the older patients is about tolerance. You’ve got an immunomodulatory agent like lenalidomide, and bortezomib. Do you combine them at slightly reduced doses; the so called ‘light regimens’?

“One has to be careful not to induce neuropathy with bortezomib. The reason is that it is the drug that you can combine with daratumumab at first relapse.

“So, if a patient develops neuropathy with bortezomib during front-line therapy, then relapses three years later, and they’ve still got some residual neuropathy, it puts the kibosh on the bortezomib/daratumumab combination option at relapse, because as soon as you restart the bortezomib, the neuropathy comes back very quickly,” Prof. Prince explained.

“This is a very important issue, so we are absolutely obsessive that none of our patients develop neuropathy, which could limit their options later.

“In older patients, you have to be careful about balancing out tolerability, and maybe offering not the full drug combinations, but delivering them separately over a period of time, because they’re better tolerated.

“I divide patients up into young, the young-old, and the old-old. The old-old certainly can’t tolerate full doses of anything,” said Prof. Prince.

He puts the approximate ages of these groups as ‘young’ (less than 70), ‘young-old’ (70-80), and ‘old-old’ (above 80).

“I jokingly say… if someone can go on a caravaning holiday, they’re not in the ‘old-old’ group.

“Frailty is a consideration. We’re going to see a more objective way of working out how we define ‘old-old’ around who can manage multiple drugs together, versus those that we have to be very careful with.

“There’s an anti-ageism thing and that’s certainly true in myeloma. It’s all about fitness and that’s why we would still offer a [autologous] transplant to some people who are 75.”

The average age of someone with myeloma is 65 to 70, and Prof. Prince highlighted “a big issue around the reality of clinical trials”, because a lot of clinical trial data is based on trial participants “five to 10 years younger than the average myeloma patients we treat.”

On being a Blood Cancer Taskforce member

Professor Prince is among the 32 members of the Blood Cancer Taskforce which is supported by the Federal Government.

“From my perspective, the Taskforce has to provide benchmarks as to what is the optimum therapy for patients in Australia and provide the appropriate roadmap so there’s equitable access to the appropriate therapies,” he said.

“What I mean by that is that patients can get access to a specialist, access to the best diagnostics, and access to drugs and clinical trials.

“The taskforce is all about providing and demonstrating what are the needs, and then, looking at the solutions. It’s not going to find all the solutions, but it’s going to start to articulate where the shortfalls are,” said Prof. Prince.

Being in the best position to fight myeloma

When a patient asks Prof. Prince what they can do to contribute to their outcome from myeloma, he tells them that being physically active (aerobic exercise) improves the immune system and poor sleep suppresses the immune system.

“I think stress and food have very little to contribute, so I tell them to exercise and look after their sleep habits, to maintain a good immune system and put them in the best position to be able to fight their cancer.

“It won’t prevent the disease, but when they’re getting their treatment, it can help give them the best chance,” he said.

“The flip side is, I see a lot of patients who are very well, who’ve looked after themselves, they kept themselves fit and they’ve done everything they can, and they get myeloma.

“I tell people, ‘don’t stress about being stressed’, and fad diets won’t change your disease.

“And, just because there’s myeloma protein, you don’t have to go crazy on the protein.

“And it doesn’t matter what your blood group is.

“A good Mediterranean diet is generally a good, healthy diet, but it isn’t going to change the myeloma substantially.”

Suggested questions to ask your haematologist

“We’ve got pretty good roadmaps for first- and second-line therapies, so asking questions about what their options are really count when patients are facing their third or fourth lines of treatment,” said Prof. Prince.

“That’s where it gets down to a number of choices and when clinical trials are really important.

“The other big question is, ‘why do I need treatment now, doctor?’.

“Patients sometimes may not need treatment or potentially could delay their treatment a bit. Understanding why they’re needing that treatment at that time is important.

“Another question is, ‘how do I know I’m doing well?’, so patients can ask about and follow their paraprotein which is about how the specialist is monitoring their disease.”

What would Prof. Prince do if he was diagnosed with myeloma?

“I’d find a good myeloma doctor, and trust them, and share the journey with them,” he said.

“The standard approach to treatment does extremely well and we’re very lucky in Australia to have access to the best drugs.

“For the first few lines of therapy, we have as good access as any other country in the world, so I feel very confident in that.

“When the disease returns, and I’m looking at second- and third-line therapies, I’d be looking at clinical trials every time.”

Advice to patients newly diagnosed with myeloma

“Find a doctor that you’re comfortable with and look for support and information; go to the Myeloma Australia and Leukaemia Foundation websites,” said Prof. Prince.

“I think patients feel well supported. You’re not alone, myeloma is more common than you think.”

Prof. Prince’s concluding comment about his overall holy grail as a clinician was, “to have a chemotherapy-free treatment so patients go through their disease treatment–whether it’s myeloma or any other blood cancer–without having to have chemotherapy”.

“That’s the holy grail, to have targeted treatments. We need it now and I’d give it to patients every day. It saves people’s lives.”

Last updated on January 3rd, 2023

Developed by the Leukaemia Foundation in consultation with people living with a blood cancer, Leukaemia Foundation support staff, haematology nursing staff and/or Australian clinical haematologists. This content is provided for information purposes only and we urge you to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis, treatment and answers to your medical questions, including the suitability of a particular therapy, service, product or treatment in your circumstances. The Leukaemia Foundation shall not bear any liability for any person relying on the materials contained on this website.