Expert interview series: Dr David Yeung discusses CML

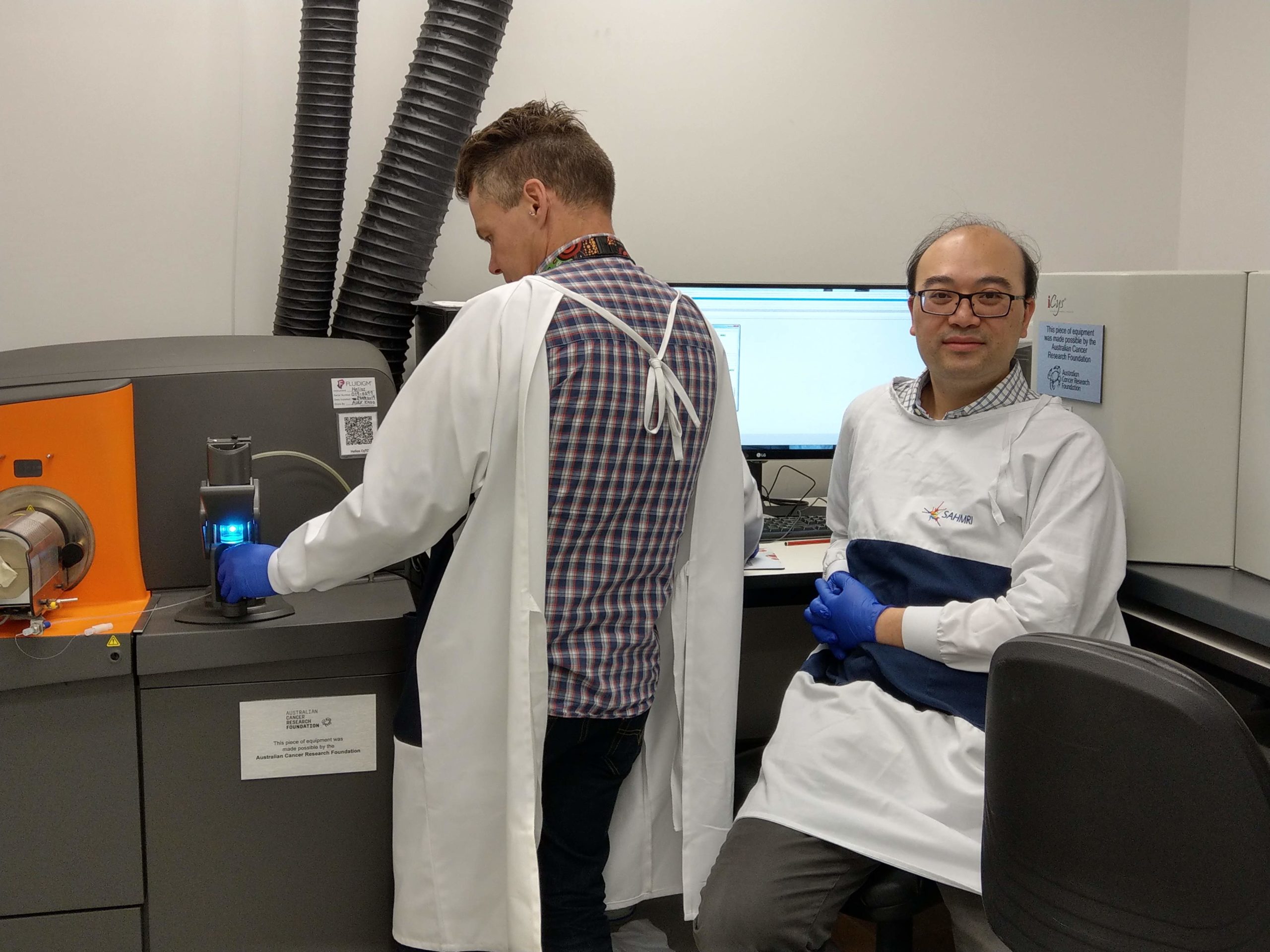

Dr David Yeung is a haematologist at the Royal Adelaide Hospital and a researcher at the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute where his main research focus is CML. He works in Professor Tim Hughes’ internationally renowned CML group and currently leads three CML studies and is about to open a new clinical trial for newly diagnosed CML.

Dr David Yeung’s interest in science and the reason he chose a career in medicine goes all the way back to his childhood in Hong Kong.

“It sounds a bit corny but it’s a desire to help people from a very young age, and even when I was very young, I enjoyed reading the health columns in newspapers and magazines,” said Dr Yeung.

“I like science. I like how advances in medicine are driven by science, and I really like the translational aspect of research. Having the two jobs, across the research institute and the hospital, enables me to combine these interests in my profession, translating the benchtop science to the patient in the clinic.”

Dr Yeung specialised in haematology because, “it is an area of medicine that is continually advancing where ground-breaking laboratory findings can rapidly evolve into treatment strategies that benefit patients”.

“You read about discoveries at a basic science level and the next thing you know you are applying it,” said Dr Yeung about the evolution and translation of discovery into the clinic.

“That’s really exciting,” he said, also emphasising, “but none of these advances occur in a flash. New therapies only come into the clinic with a lot of hard work and persistence from a lot of people”.

At the other end of the spectrum, there’s the human aspect of medicine.

“You’re looking after patients over the life of the illness,” said Dr Yeung.

“In haematology, many of the illnesses we look after, such as acute leukaemia, have a high mortality rate, but it’s a privilege to be able to try and help patients through the most difficult times in their lives.

“With the availability of better treatments, an increasing number of patients do well. When they get to live a long and normal life, and can be with their families, it’s very gratifying and that is the ideal situation.”

Stats and facts about CML

Roughly 300 new diagnoses of CML are made across Australia each year, but with life expectancy for CML patients now approaching that of the general population, Dr Yeung expects the number of CML patients to grow year by year, so the prevalence of CML will increase as this group of patients age.

“The median age of diagnosis is 50-55, so these are middle aged patients, with slight male preponderance, but not by much,” he said.

Whether CML is a hereditary disease is a question Dr Yeung addresses with his CML patients if they are concerned about passing it on to their children.

“I don’t think there’s any convincing evidence that CML, in and of itself, can be passed from one generation to another,” he says.

“CML is caused by a very specific fusion gene called BCR-ABL; the BCR gene with the ABL gene, and that’s not inheritable. However, there are families with inheritable genetic defects that may increase the risk of blood cancer in general.”

A brief 20-year history of CML

The first tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), imatinib (Glivec®) was the first targeted treatment for any cancer. This drug became available 20 years ago. CML treatment options prior to the introduction, of imatinib included interferon, and chemotherapy drugs like cytarabine and hydroxyurea.

“In that era, you either used those somewhat crude therapies or you performed an allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) for CML patients,” said Dr Yeung.

“If you didn’t have a transplant, the CML progresses to a more aggressive leukaemia which you would need to treat like AML (acute myeloid leukaemia). And if you did a SCT, you could cure the patient, but there was such a high risk of death associated with the transplant process, not to mention the multitude of potential complications,” he explained.

“Then imatinib came in and very quickly haematologists noted significant and dramatic clinical responses in CML patients. But there were also reports of treatment resistance related to BCR-ABL mutations.

“In the early days, no one was sure how much of a problem resistance was going to be. It turned out that if you used imatinib reasonably early in the course of the disease – such as in newly diagnosed patients – it worked very well and prolonged survival by decades.

“However, some patients did have side-effects to imatinib. Intolerance and the mutations/resistance issues spurred the development of better BCR-ABL inhibitors – dasatinib (Sprycel®) and nilotinib (Tasigna®).

“These second generation TKIs are more potent than imatinib and can treat imatinib-resistant disease. They also offer patients with side-effects an alternative agent which they may be able to tolerate. The second generation TKIs became available to Australian patients through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) about 10 years ago; that was the next breakthrough in targeted treatment for CML patients,” said Dr Yeung.

“Around the same time, there was work to show that in patients who were successfully treated and had undetectable disease for a very long time, about 50 per cent could safely stop therapy and not need tablets again.

“This work, stopping studies specifically, was pioneered here, in Adelaide, by Tim Hughes and David Ross, together with Francoise Mahon and Delphine Rea from the French CML group. Patients who have achieved close to, or undetectable BCR-ABL, and successfully stopped their drug have achieved what we now call treatment-free remissions (TFR). This was a seminal discovery.

“Before that, everybody was too scared to take patients off drugs. We thought that stopping therapy would lead to a high rate of relapse, and that relapses may be fatal. The flip side of that is, you had an increasing cohort of patients who needed to be on therapy for life and some had low-grade chronic toxicities that affected their quality of life. There was also the cost issue for the [health] system.

“TFR is now a central theme of CML research – how can we predict when patients are ready to come off their tablets and how to maximise the probability of these patients not needing therapy again,” said Dr Yeung.

“TFR is one of the consumer-driven agendas in CML research because an increasing number of CML patients in Australia are going to live a long life, and they going to live well. But if they’ve got chronic side-effects for 20 years that are lifestyle-affecting and causing them to be miserable, they will ask, ‘Doc, when can I get off these dreadful pills?’

“A number of patients don’t have any side-effects and that’s fine, but still, a pill is a pill, and if you can tell them, “Mr Smith, there’s a 95 percent chance you won’t need this tablet again if you stop next year because of the clever test that I’ve done and the result shows this is what it is”, then Mr Smith can make his call.”

Second/third generation TKIs and side-effects

The second generation TKIs are more potent than imatinib, with a lower likelihood of leading to the development of mutations.

“They’re quicker to act and reduce the BCR-ABL leukaemia cell numbers more quickly compared to imatinib,” said Dr Yeung.

But some patients may have unacceptable side-effects, which are “actually quite dangerous”. Dr Yeung said there was “a slightly higher chance” of problems in susceptible patients with blocked arteries that could lead to a stroke or heart attack from nilotinib, and fluid around the lungs [pleural effusion] that affects breathing, with dasatinib.

Whereas the side-effects from imatinib are “annoying” – facial swelling, nausea, diarrhoea, vomiting, swelling of the ankles – “these tend to be less serious health consequences, but they are more common and affect quality of life”, said Dr Yeung.

“When we treat CML, we’ve got to balance who goes on what drug, depending on the likelihood of our patients developing side-effects and how this may affect them – actively taking into account other chronic health problems a patient may have.”

Dr Yeung said another issue was that some patients developed disease resistant to the second generation TKIs, and five years after nilotinib and dasatinib, ponatinib (Iclusig®) became available through the PBS in 2015.

“This is a drug we reserve in third line because, while it’s very potent against CML, it’s also got the highest chance of causing blocked arteries. We only use it under special circumstances when we have no other choice. This is reflected by current Medicare restrictions for its use in the third line (after patients are either resistant or intolerant of all other TKIs available in Australia).”

Dr Yeung said the more potent BCR-ABL inhibitors can be used for increasingly resistant disease, and sometimes, when patients are intolerant to one drug, “we swap across to another drug and most of the time the side-effects resolve”.

“So, it’s nice to have a choice, to have more than one agent to rely on.

“We’re also working towards the goal of having a really potent BCR-ABL inhibitor without the side-effects. We’re always looking for a better agent to fill the gap,” said Dr Yeung about ongoing research.

Asciminib study as a frontline therapy

Asciminib is a new drug currently undergoing clinical trials for CML. The results of the first clinical trial associated with its use was published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year, in a clinical trial led by Professor Tim Hughes.

“In Adelaide, we’ve had access to asciminib for about six years because of our active clinical trials program in CML. There are a number of our patients who have had resistance or side-effects to all the TKIs that are currently available, and it’s great that have another option to offer these patients.

“Even in this group of patients with resistant disease, we’ve been seeing some good results; there are patients with a very good reduction in their CML, and the side-effects profile seems quite favourable, although we still need long-term data.”

Dr Yeung said preparations were being finalised for a Phase II Australasian study run through the Australasian Leukaemia & Lymphoma Group to test asciminib in newly diagnosed CML patients.

Recruiting for this trial, called ASCEND-CML, will start in late-2020, with at least 15 sites to open across Australasia, including at least one hospital in each state and territory.

“What we hope to achieve is disease burden reduction and disease response as favourable as any other anti- CML drug currently available, but without the side-effects of the more potent TKIs, with the ultimate goal of getting more patients to the starting line of the treatment free remission phase of the journey.”

What the optimal patient journey looks like

Dr Yeung said the patient journey “arguably, looks something like this in the optimal sense”.

It starts off with “rapid diagnosis, which we have in Australia, where almost every state and territory has access to multiple laboratories and can diagnose CML well”.

“Then, the patients need access to specialist physicians, and sometimes clinical nurses, for advice on diagnosis and to choose a drug to start therapy with. The patients will then have the drug,” he said.

“They can then watch their CML leukaemia burden fall (using the BCR-ABL QPCR), with monitoring through a credited laboratory; and most patients have access to that. We want the CML burden, measured as the BCR-ABL level, to ideally drop to undetectable levels as soon as possible, allowing patients to have the option of TFR.

“At the moment, patients who choose to have a TFR attempt have a ~50% chance of not needing therapy again, although there is no sure way to tell, ahead of time, what the success rate will likely be in any individual patient.

“In the future, we will have a suite of tests that can tell if the patient can come off their drug and never have to go back on tablets, or not.”

Treatment-free remission

After reaching a deep and stable response to treatment, Dr Yeung said most patients, when offered a chance to discontinue TKI therapy, do choose to stop their treatment provided they have the information, the opportunity to think about it, and the support.

When broaching the topic of TFR, Dr Yeung said, “almost invariably, patients show an interest and want to know more”.

“We talk about the success rates, the possible side-effects of coming off their CML drug, and what to do if the disease comes back.

“A number of patients prefer not to do it: the possibility that the disease may come back, and the uncertainty regarding the timing will place a psychological stress on certain patients.

“They may defer that decision, but eventually most patients get to a point where they’re comfortable in considering a trial of cessation if the support network is there,” said Dr Yeung.

“Patients want to know that yes, you are testing them regularly enough to look for signs of relapse, yes someone will check the reports when they come through, someone will tell them if the result is positive or not, and someone will tell them if they need to restart their drug.

“If they’re reassured that… there’s someone to call, someone who’s checking, and that there’s nothing to lose by doing it, then patients are generally happy.”

Dr Yeung said when patients come off their CML drug, they should, at a minimum, have a monthly blood test for six months, then every two months for the next six months, and then every three months thereafter and forever.

“There have been rare cases around the world of patients where restarting the therapy doesn’t work so well, but the vast majority of patients do respond very quickly,” he said.

Initial disease control critical

Another of Dr Yeung’s colleagues in Adelaide, Professor Sue Branford, was one of the first people who developed an internationally standardised BCR-ABL monitoring assay to approximate the number of CML cells left inside a patient. Having an accurate assay is critical in telling patients and doctors how well their anti-CML therapy is working. There is now a series of treatment targets at various time points that patients should meet after starting treatment if they are to do well.

“Sue has 20 years’ of BCR-ABL data in her lab. Her observations show: how the disease responds in the first three months is critical to longer term responses,” Dr Yeung explained.

“Analysing that data and working with Sue, our colleague Dr Naranie Shanmuganathan, found that that if a patient starts therapy and their BCR-ABL (disease burden) falls like a lead balloon, that’s really good because it means you’ll get to your goal of zero CML faster, and when you are eventually advised to stop the drug, you’re much more likely to not need to get back on it.

“If the BCR-ABL falls slowly, even if you eventually get it down to undetectable levels, and your doctor says you can try coming off tablets, the disease is much more likely to relapse.

“Whether it takes you three years or one year to get to the starting point of a trial of cessation, it’s still zero or close to it before you stop. But what is interesting, is the patient who had a fast disease response within the first three months of starting treatment and got to the TFR starting point much sooner, will have a higher chance of not needing treatment again, as compared to the patient who had a much slower rate of response in the first three months, and took longer to get to the starting point. Naranie is about to publish her paper on this,” explained Dr Yeung.

“One interpretation of the data is that the initial disease control is critical, and getting a drug that is potent and non-toxic to actually bring the tumour load rapidly down in that initial period may actually set you up for success later on.

When to have a go at treatment-free remission

The current recommendations state that CML patients should achieve good control of the disease with their anti-CML therapy – also called deep molecular response – and have maintained this with therapy for at least two years, prior to being considered eligible for coming off therapy for a TFR attempt. The total duration of therapy should be at least three years prior to stopping. Patients are advised not to stop treatment if these conditions are not met, and never stop therapy without consultation with their doctor.

“If a patient has had two years of undetectable BCR-ABL and more than three years of treatment overall, if they are happy to have a go at TFR, we would supervise them in a structured trial of cessation any time they are ready. Any additional year of treatment, whilst maintaining a deep molecular response, is likely to increase the success of stopping, though not by much.

“Sue Branford published data about six years ago to say that if you start off with imatinib treatment, after eight years of treatment 42 per cent of patients will reach the point where you would offer a treatment-free remission attempt.

“This may very well change in the future and the hope is that we can shorten this time significantly,” said Dr Yeung.

“The expectation is that, with more potent drugs, we wouldn’t take eight years to get 42 percent to the starting line of stopping. It may take three or four years, and that’s what we’re seeing with the more potent drugs like nilotinib or dasatinib. Hopefully we can do better still.”

Asciminib in combination with other CML drugs

Since asciminib is in a completely different class of drug to imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib, Dr Yeung said, “arguably you can pair asciminib up with the drugs we currently have, to try to hit CML in two different places”.

“We still don’t know how effective asciminib is in resistant disease. “There is ongoing work pairing asciminib with the other TKIs in those patients. Although the ASCEND-CML patients will enrol newly diagnosed patients, there is provision for them to access combination therapy if they fail to respond to asciminib alone. In that setting, asciminib may be paired with either imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib.

“We think that combination strategy may work much better in patients with treatment resistance. How to optimise outcomes in resistant patients is another clinical research priority in CML. In this group, we think that combination is the way forward.”

Four clinical research priorities

Dr Yeung said the clinical research priorities in CML were:

- how to get better, safer, more effective treatments for the newly diagnosed

- how to improve salvage in those who have a suboptimal response and disease resistance

- how to increase the number of patients we can treat successfully, and predict when patients are ready to come off therapy and get off therapy, and

- improving the success of a second trial cessation.

And biologically, there are a number of interesting research topics, such how the BCR-ABL gene forms in the first place; how CML cells take up oxygen and nutrients compared to other cells, and whether this can be exploited to develop new therapies; and how the immune system affect treatment responses.

“These are some of the things we’re following up on, so watch this space,” said Dr Yeung.

Last updated on January 3rd, 2023

Developed by the Leukaemia Foundation in consultation with people living with a blood cancer, Leukaemia Foundation support staff, haematology nursing staff and/or Australian clinical haematologists. This content is provided for information purposes only and we urge you to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis, treatment and answers to your medical questions, including the suitability of a particular therapy, service, product or treatment in your circumstances. The Leukaemia Foundation shall not bear any liability for any person relying on the materials contained on this website.